Personalizing nursing care to engage patients: Webinar shares the importance of finding your own joy first

We know communication, respect, empathy, organization, and lifelong learning are crucial functions of nursing—but what about the ability to find your own joy?

Jill Ellis, Solutions Expert, Magnet and Nursing Leadership, recently addressed this topic in a webinar that offered insights on helping nurses survive in an ever-changing nursing world. With 40 years of nursing to her credit, Ellis’ insights are powerfully astute.

“Finding your own joy means replenishing yourself, recharging your battery, thinking about yourself as a nurse,” she advises. “It’s about taking a few minutes to reconnect with yourself, taking some time in the breathing—in through the nose, out through the mouth—closing your eyes and centering yourself, and being mindful.

“Sometimes it’s making connections,” she adds. “It’s going out and spending some time with friends. That can help you recover as well. Nature, going on walks, swimming—those things can be important. Music, expression, maybe through dance. What are those things that can help you find gratitude?”

Ellis believes that joy is internal and inside of us all. She says that as nurses, we must find a way to rekindle the joy and bring that passion and fire back to give personalized nursing to each patient we serve.

First Things First

Ellis says that the personalization nurses give patients starts with compassion. She recalls a time when she was a director of nursing and had become downtrodden and lost her motivation.

“I just did not like my job,” she says. “I would have so many complaints or concerns. My cup would not be half full. My battery would not be charged. And I would think, ‘I’m going to find someone to see if I can rekindle my joy.’ And I would go to an 80-year-old patient’s room and ask permission to talk to her and sit on her bed. And I would pat her hand, and I would ask her about her care. Nine times out of 10, it was great; she thought everyone was so wonderful. Hearing her voice telling me the good things we were doing brought my joy back up. So that compassionate moment really did give me a way to connect to the patient and recharge my batteries.”

She says it’s important to consider ourselves first as nurses, because HCAHPS results are not getting any better across the country.

“I must ask the question, why?” she says. “Why are we not moving it ourselves as we move forward? The primary driver in HCAHPS, really for the last 12 years, has been nursing. So why would nursing be of such primary importance in the hospital setting? Is it because patients are there for the 24-hour nursing care? They’re there for their antibiotics or IVs, tests, and treatments, yes—but they’re really there for the nursing care.”

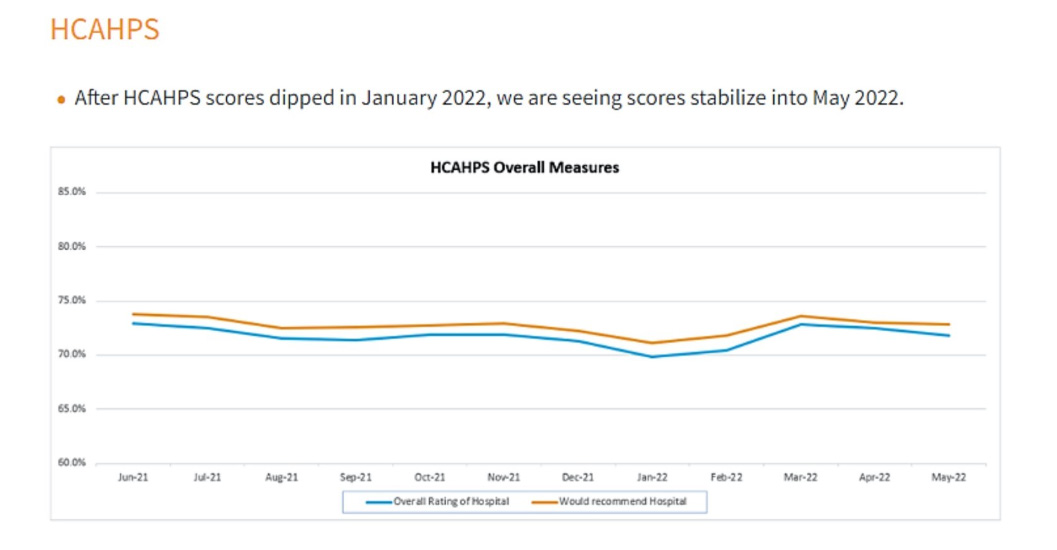

From June 2021 through May 2022, Ellis says HCAHPS overall measures were fairly flatline.

“It boils down to nursing communication,” she says. “It boils down to me as a nurse. So what am I doing myself? If we think about that and internalize it, we must consider how we practice nursing. What are we doing from the nursing perspective first? I encourage us all to think about things we can do better. You may have tried this in the past, but you may have to dust it off and think, ‘Can I try it again for the future?’”

Embracing Kindness

Ellis suggests that nurses should treat themselves with kindness—because while we all think sometimes that we can control everything, we can’t. “I’m here to give you relief, a sense of grace,” she says. “There are things you can, and there are things that you can’t control.”

And while there are many parts of care nurses can’t control, Ellis emphasizes that there are certainly things they can—like the boundaries they set for themselves, their response to others, how they speak to others, and the energy they give.

One successful strategy she relates is, when an employee comes into your office to complain about a coworker, to listen to their complaint and follow up with, “So I hear that. I’ll have a conversation with that colleague. Let me ask you this question: what part did you own?”

Other areas to refresh are the use of empathy and empathetic gestures. “You can always say, ‘I don’t know’—which is honest—‘but I will get you an answer,’” she says. “So finding a way to follow up and follow through with our patients is important. Listening is important. Especially with the intent to learn.”

The ability to remove assumptions is also critical, she says. Ellis remembers a time when she worked for an urgent-care children’s healthcare center that was open 10 a.m. to 10 p.m., seven days a week.

“There were days when we might have up to 120 patients in a little more than 12 hours, with one doctor and two nurses,” she says. “That was very challenging. I know wait times have been extreme in the last couple of years, but we would have a three-to-four-hour wait.

“Now, if you have children and they’re not feeling well, they’re wailing and gnashing teeth in the waiting room and around all the other kids, and then you put them in a small room to see the doctor that doesn’t make them feel better,” she continues. “I assumed, ‘I’m a mother; I’ve had children. I wouldn’t want to be in that room longer than I have to be. So when I go in there, I’m going to give them instructions as fast as I can to get them out the door, so they’ll be happy. They will love it because I’m so fast, and they’ll be able to leave.’ But you know what? They didn’t. They wrote back in comments saying that I was uncaring and abrupt. I wasn’t the person I thought I was trying to be in those conversations.”

Ellis says her leader had a very tough conversation with her and said, “Either you fix it, or you can’t work here.” At first she cried and was very distraught—but she took a month to think about it, and figured out what she could do better.

“I learned to sit on the edge of the chair in the room, which implies time,” she says. “I learned to look up and smile, and then ask them at the end, ‘Is there anything more I can do for you?’—and, if possible, let the patient start to stand up before I did to leave.

“It didn’t take more time, but it was a better way of spending the time,” she says. “So there were no assumptions. I incorporated the patient’s feedback into my practice, and it made a big difference. All those comments stopped as well. It’s a way for us to think about this question: we know what should happen, but do we know what should happen from the patient’s perception?”